Please note: this article got from me a complete rewrite in August 2025.

I’m a little short of breath because it’s been a long day and I have been breathing all the time. As I was breathing, I was thinking and writing. Would you care for a short, entertaining read? Yes? Too bad. Let’s plough through.

How Can I Be Educated?

(Including, but not restricted to, the accidental confession of a fifty-year-old who took imaginary walks with dead men)

I once believed one piled books on the night-stand until wisdom bled out. It does not. After mid-life slammed its trinity of knocks—metanoia, conscience and the unanswerable “what now?”—I stood in the rubble muttering the old punch-line: teach thyself. The joke, as I finally saw, is that if one is uneducated there is no one left inside to do the teaching. Therefore the only honest question becomes, “Who will educate me?”

Step one: qualify the quarry

Romano Amerio warns that truth is not manufactured but discovered, insists the pupil cannot haul his own empty mind into presence. Good—and about as useful as a theology textbook floating across a storm. Romano Guardini is warmer: knowing is touching, eating, marrying. Now the hint becomes palpable—there must be contact. Ivan Illich wraps it in scent: one must smell the master, slip into the aura where friendship catches like damp on wool. Read the pages, taste the paper, but do not yet call it education.

Step two: answer Nietzsche’s telegram

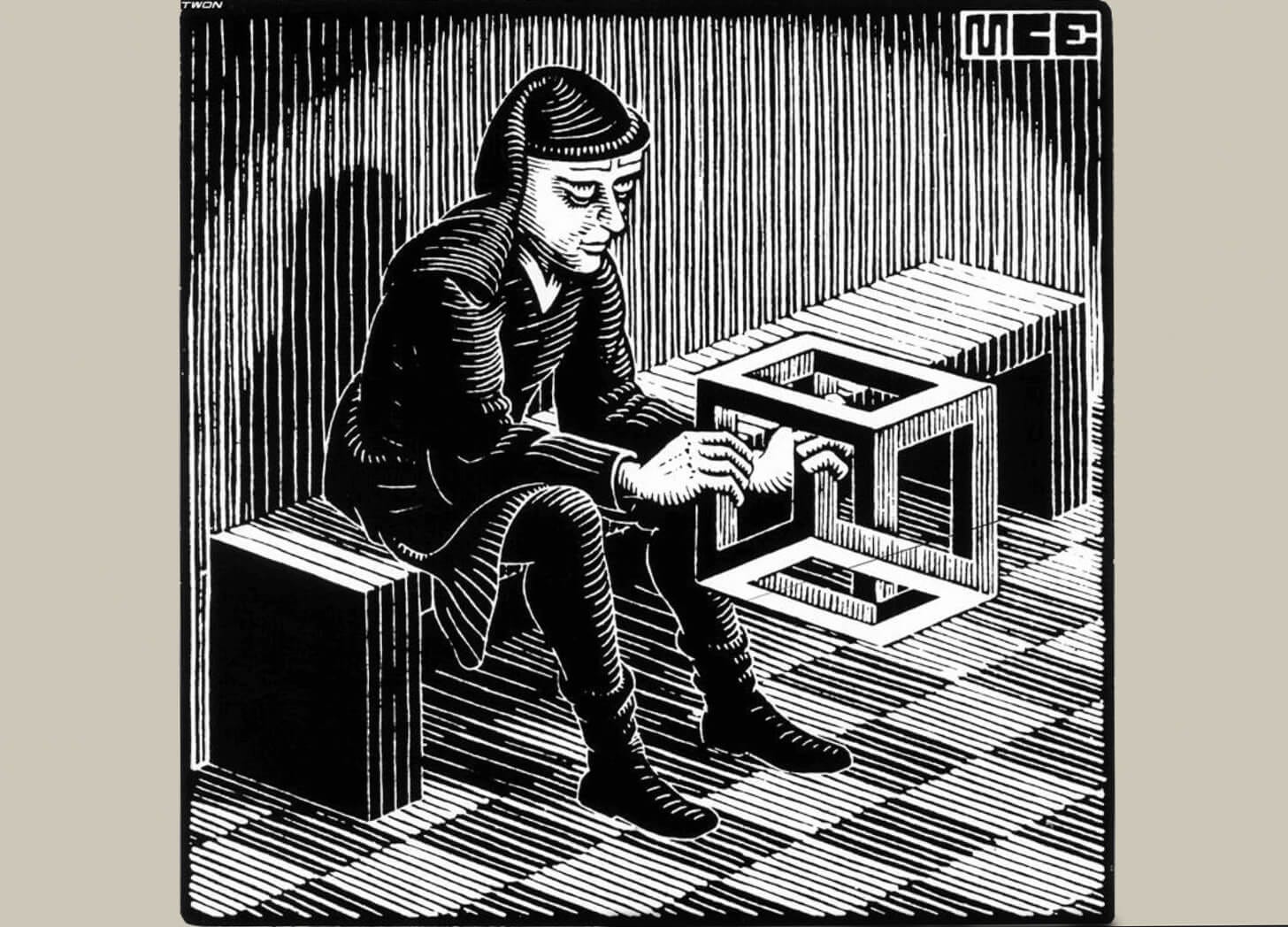

Friedrich alone, ancient friend of contradiction, claims an educator is above all a means by which we rediscover ourselves—and then locate that self as friend in the figure of Arthur Schopenhauer. Allegro possible, but only if one is willing to make the long march off the page and into imagination. Therefore I do a rational man’s mad act: invite Schopenhauer—dead, bearded, grumpy—to tea. I set beside me his photograph, as children do with teddy bears for protection from the dark. Instead of dissecting paragraphs, I let them dissect me. I open the book; he begins to speak.

The remedy (skip here if you dislike gear-shifts)

Bookmark becomes bell-pull. Every text is appointment: my mentor waits at an hour I designate.

Recordings, if any, are involuntary séance. Thirty seconds of his voice is enough phonograph to borrow lungs.

Biography is pilgrimage. I rent the spare room of his habits; the crinkle of daily newspapers, the continental hush of a unheated study.

Silence is the interval where the friendship ferments. I walk imaginary streets beside imaginary cloaks.

What happens is irrational and, in consequence, real. I keep appointments, keep memory, keep finishing books. The text no longer talks at me; the man talks to me. Suddenly I study like a devotee, finish like a lover, recall like gossip. The stuffy syllabus has turned into colloquy.

Practical coda (with none of the dreary practicality)

— Invite the dead professor with ceremony: a candle, a favorite chair, a photograph angled to catch conversation.

— Do not annotate first morning. Listen. Choose one sentence to carry like a pocket-stone through the day, rubbing it against circumstance.

— Archive his voice in kind ears and hard recollection: a clipped interview, a passing anecdote from memoir. Replay until it feels like déjà vu.

— Let the new day breed new friends: Augustine slips after Schopenhauer, Weil after Augustine, like dancers passed hand to hand at a court where the host is time.

Do not mistake this for cosy occultism. It is simply the old faculty of attention dressed up as hospitality. And when attention scabs over into affection, education has already happened; the two are inseparable.

So I kiss you on the mouth, dear reader, before you leave to assemble your own spectral faculty. The library is crowded; the dead are waiting to speak, but only to those willing to carry their chairs closer until the room smells faintly of cigars, salt air, or whatever the master exhaled. A teacher arrives as aroma, friendship matures as scent, and presently you discover the unlovely clutter of your own mind has arranged itself into conversation—you have been educated.

Appendix

Here, then, is the knot I am still unpicking. When the educator and the one being educated meet so completely that they can complete each other’s search for what truly belongs together, we may have stumbled into the very dynamic that once quieted St. Augustine’s ache to be made whole with his Creator. How that happens is still a mystery to me, and it waits for another day. For now, I lean solely on Nietzsche’s long final word, trusting that these lines may carry the impatient grace that could still disperse the fog of modern alienation in (our absent) adult education—and in everything else.

“I see above me something higher and more human than I am; let everyone help me to attain it, as I will help everyone who knows and suffers as I do: so that at last the man may appear who feels himself perfect and boundless in knowledge and love, perception and power, and who in his completeness is at one with nature, the judge and evaluator of things. It is hard to create in anyone this condition of intrepid self-knowledge because it is impossible to teach love; for it is love alone that can bestow on the soul, not only a clear, discriminating and self-contemptuous view of itself, but also the desire to look beyond itself and to seek with all its might for a higher self as yet still concealed from it. Thus only he who has attached his heart to some great man receives thereby the first consecration to culture; the sign of that consecration is that one is ashamed of oneself without any accompanying feeling of distress, that one comes to hate one’s own narrowness and shrivelled nature, that one has a feeling of sympathy for the genius who again and again drags himself up out of our dryness and apathy and the same feeling in anticipation for all those who are still struggling and evolving, with the profoundest conviction that almost everywhere we encounter nature pressing towards man and again and again failing to achieve him, yet everywhere succeeding in producing the most marvellous beginnings, individual traits and forms: so that the men we live among resemble a field over which is scattered the most precious fragments of sculpture where everything calls to us: come, assist, complete, bring together what belongs together, we have an immeasurable longing to become whole.”1

Thanks for reading my stuff. I have written such a long post because I have been busy being educated and haven’t had time to make it shorter.

Tomasz Goetel

25 January, AD 2022

Ibiza, Spain

The quotation is taken from Nietzsche’s Untimely Meditations (“Schopenhauer als Erzieher”—”Schopenhauer as Educator”), the third of the four “Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen,” sections 6 and 7 in most modern editions.