Ivan Illich’s “The Political Uses of Natural Death”, (1974)

The historical, social, and ethical dimensions of death. A reflection on the impact of societal norms and medical practices on modern man’s most personal and inevitable experience

“I have argued on other occasions that the crisis of the school system cannot be solved by recourse to more and better education inside or outside of schools. I have equally argued that the crisis of traffic systems cannot be solved by a changeover to rapid transportation tax-free or fare-supported. I will now argue that the crisis in medical institutions cannot be solved by their reorganization under public or under professional control. As long as these large service industries remain subservient to quasi-religious goals such as universal education, higher speed, or better health, the only effect which their reorganization can have is to provide more luster to these myths and more professional exploitation. It is not the industrial but the ritual nature of these institutions which must be brought to the fore; it is their power to generate expectations which by definition they cannot meet which must be clarified. In the case of medicine this can best be done by focusing on the historical evolution in the course of which we have constructed that social reality of health which now constitutes medicine’s defining purpose.”—an excerpt from the full text below.

Dear Flying Fish Reader,

Tomasz Goetel here.

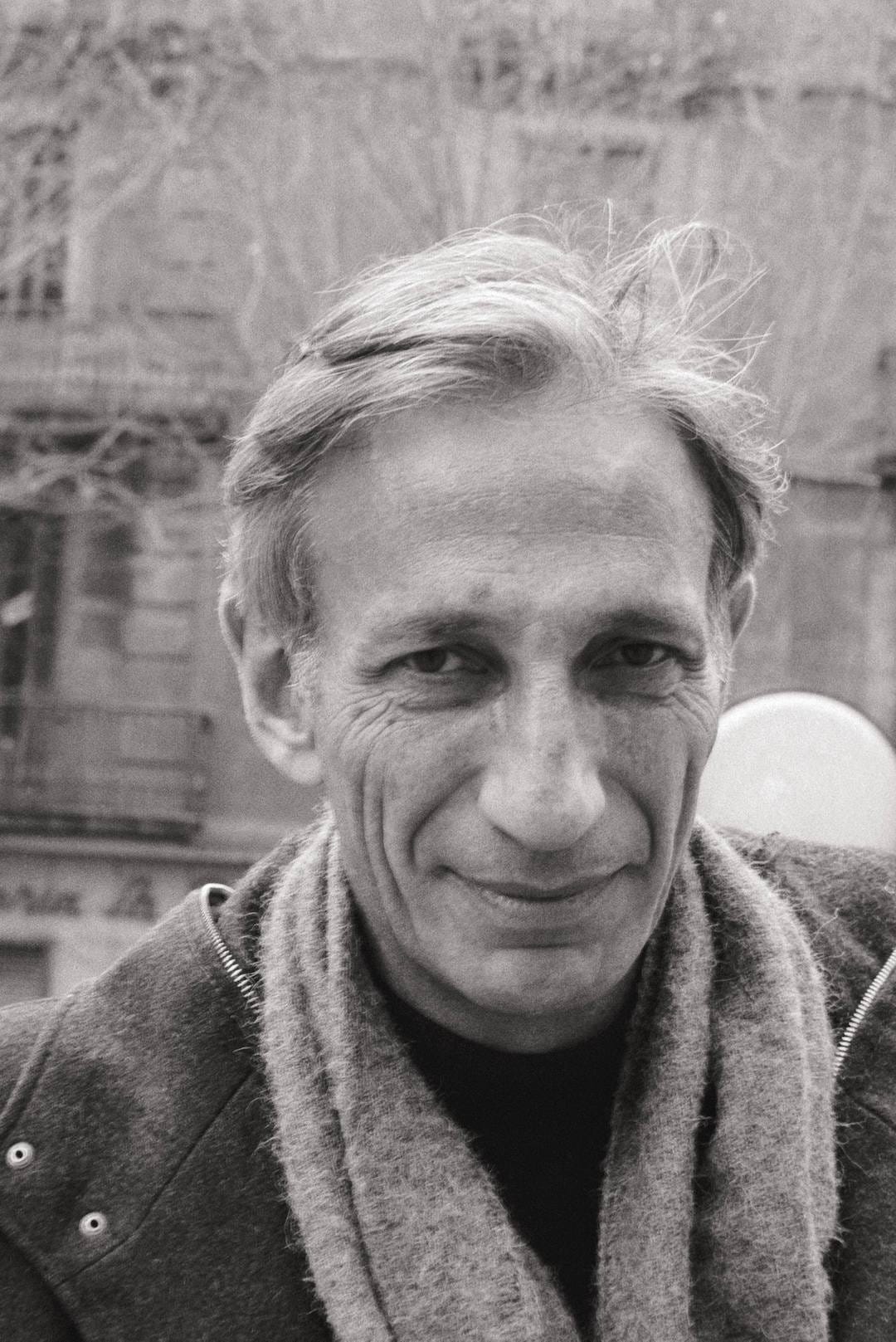

Ivan Illich (1926–2002), born in Vienna, was a Roman Catholic priest and theologian. He is often misread as a”social/ or cultural critic”, “historian”, etc. As far as my, rather extensive, reading of Illich shows me, there’s no way that Illich might have described himself as a “critical thinker”. Nevertheless, he may be known (fair enough) for his profound critiques of modern institutions and systems, reflecting a deep concern for man and man’s place in society.

Ivan Illich was a polymath, fluent in multiple languages; he had a unique perspective on the role of technology and systems in society, often focusing on their impact on human autonomy and community life. Illich was also a high-level non-conformist. Here at “The Flying Fish”, we also see him as a our friend, our educator, our favourite theologian and poet.1 We see Ivan Illich as a (self-described) xenocryst, akin to the flying-fish paradox.2

Illich’s essay (presented in full below), like much of Illich’s writing and speaking, is not widely known. But let’s say it straight out: I am struck by the seriousness and depth of this essay.

In this particular text, Illich explores the concept of natural death and its political implications. He critiques the medicalisation of life and death, arguing for a more humane and less institutional approach to the end of life. But those are not the reasons why I am re-publishing Illich’s piece here. The Flying Fish and I bring Illich to speak his mind because we want to read texts and hear voices of those who have something help-full to say about man’s personal and most important act: the act of dying.

Let us attend to this text, originally published in 1974.2 Illich’s insightful analysis is not just a critique but a call to re-envision the approach to being-alive’s final chapter.

Thanks for reading “The Flying Fish”. I kiss you on the mouth.

Tomasz Goetel

Ibiza, Spain

24 November AD 2023

Source text: The Hastings Center Studies, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Jan., 1974), pp. 3-20 (also available for download here). Source text formatting, including Ivan Illich’s footnotes (numbered from 3 to 45), has been humbly done by Tomasz Goetel. The first two (1-2) footnotes are written by Tomasz.

The Political Uses of Natural Death

by IVAN ILLICH

In any society the dominant image of death determines the prevalent concept of health. In modern societies two contradictory concepts of death are simultaneously held, and this contradiction is accentuated and perpetuated by Janus-faced medicine. As a productive industry medicine is organized like an agency for the defense of mankind against a host of evil deaths, while as a world-wide ritual it is structured to foster the belief that natural extinction from peaceful exhaustion is the birthright of all men.

The Crisis of Medicine

The ritual nature of modern health procedures hides from doctors and patients the contradiction between the ideal of a natural death of which they want to die and the reality of a clinical death in which most contemporary men actually end. The concept of health is defined idealistically in reference to the former and the idea of sickness is an ambivalent relationship to the two. The crisis of modern medicine can be faced only if this hidden contradiction is brought to light.

Public confidence in medical practice is close to a breakdown while just at this moment public dependence on medical care has reached unprecedented heights. People learn to depend on medical guidance for their food, their feelings, and their sex life, and at the same time discover that they have been damaged with the approval, or on the prescription of, doctors. As a consequence, attention is focused on the crisis in medical services while the much deeper crisis of medicine as a ritual agency amalgamating worldwide beliefs is pushed into the blindspot of social vision.

I want to focus on medicine as a ritual supporting a destructive myth and I want to avoid getting side-tracked into remedies which can improve the performance of medicine as an industrial enterprise.

Superficial Explanations

Remedies for inefficiency are usually sought in three categories of institutional defects: self-interested production of services, unjust delivery of benefits, and a professional monopoly over health care. This monopoly takes two forms: the exclusion of para-professionals from independent practice, and the imposition of allopathic medicine over all other persuasions.3

1. The collusion of doctors, pharmaceutical firms and hospital administrations is the first shortcoming which has attracted attention. It is true that modern medical services are usually operated by self-seeking professionals;4 that delivery of health services is operated on feudal patterns; that research is conducted to perform miracles rather than face widespread needs; that failures of bio-medical intervention are hidden by blaming the patient, his culture or his government for his unwillingness to learn, to respond, or to survive; that total iatrogenetic damages grow faster than demonstrable benefits.5 As each of these forms of malpractice becomes more common and more blatant, the demand grows for more correction by public control. And each correction in turn provides more prestige to the medical product and more trusting dependence on the part of the consumer.

2. It is equally true that delivery systems in most countries are very unjust. Even after twenty years of socialism, the Chinese had to admit to a gulf between hospital-based, industrially-produced medical care for the few, and high-handed malpractice for the masses. After the short euphoria about nonprofessional, barefoot but modern healers, the new concern with international competition over miracle cures again concentrates benefits on those whom the doctors select. Everywhere, those on whom doctors can practice their virtuosity get disproportionately more attention than others. But this is not the only reason why health services, which are financed largely from taxes, are then cornered by the few. In capitalist economies, the rich transform medicine into a system of regressive taxation by using slight personal funds to purchase an edge of large public resources.

In South America hospitals supposedly private are often 80 percent supported by public funds. Social Security in Mexico is unable to overcome the inequitable distribution of medical services. Three percent of the population have access to what is, probably, the world’s record in combining personal care with technological excellence. They are government employees who have truly equal access to ISSTE, whether they are ambassadors or drivers. To these 3 percent of privileged consumers, one-third of the country’s hospital budget is allotted.

Other minorities are age-specific. The old in the U.S. constitute 10 percent of the population and consume 20 percent of health services, overwhelmingly for the treatment of arthritis, loneliness, cancer and other afflictions for which modern therapy cannot be shown to have either healing or soothing effects.

As public dependence on professional services becomes stronger, each of these forms of maldistribution becomes more irritating and, therefore, amenable to some management under protest. And each improvement of delivery increases total costs, spurs demand, and tends either to lower quality or to increase damage. The crisis of health delivery is, of course, analogous to that which we know from other industrial enterprises, each organized as a public utility and each defining its output as a basic necessity. More people develop tastes for increasingly more costly products, then learn to define them as basic needs, and soon their demand outruns the limits inherent in the method of supply. More people use vehicles, and block traffic for more people. More people get college degrees, and many more suffer by being defined as dropouts. More people want places in ambulances, hospitals and clinics, and the few who get them ask for increasingly more costly services. As the consumer pressure rises, society is so reorganized that the nonconsumer can no longer satisfy his simplest needs in traditional forms. Folk healers disappear and home remedies disappear soon afterwards. You cannot get to work without first consuming transportation, not get a job without first consuming education, not get the simplest medicine without first consuming the doctor’s time who prescribes it. Agitation for more deepens the conviction that you can not do it on your own.

3. Higher quality in production and greater equity in distribution translate into higher professional controls. The resulting professional monopoly constitutes the third explanatory paradigm for the present crisis in medicine. This third paradigm enables criticism to go further than the previous two. It exposes the damage which contemporary medicine causes by its restrictions6 on the nurse, the midwife, the bone-setter and the tooth-puller, by its discouragement of self-care, and by disparagement of the heterodox healer.7 But just like faulty production and unjust delivery, so professional monopoly indicts medicine as a productive industry and not medicine as a mythopoetic ritual. It explains scarcity of outputs, not absurdity of shared beliefs. More self-care, acupuncture, astrology, radiesthesia, and yoga can be incorporated into a culture which wants to transform the world into a cosmic hospital for lifelong patients, just as contemporary bio-medicine can be used for the cure of self-reliant people.

Health care now is scarce, unjustly distributed, and prejudicial to self-care, and these defects keep iatrogenic damage within bounds. Improved outputs of a health-care system could render it—to use the phrase literally—more sickening. As long as medical practice supports society’s death-oriented image of health, medicine will remain destructive.

Health in the Shadow of Death

I have argued on other occasions that the crisis of the school system cannot be solved by recourse to more and better education inside or outside of schools. I have equally argued that the crisis of traffic systems cannot be solved by a changeover to rapid transportation tax-free or fare-supported. I will now argue that the crisis in medical institutions cannot be solved by their reorganization under public or under professional control. As long as these large service industries remain subservient to quasi-religious goals such as universal education, higher speed, or better health, the only effect which their reorganization can have is to provide more luster to these myths and more professional exploitation. It is not the industrial but the ritual nature of these institutions which must be brought to the fore; it is their power to generate expectations which by definition they cannot meet which must be clarified. In the case of medicine this can best be done by focusing on the historical evolution in the course of which we have constructed that social reality of health which now constitutes medicine’s defining purpose.8

Health has become a multifaceted concept. It means different things to the geneticist and the clinician, for public hygiene and individual treatment, for the patient who feels ill and the doctor who defines his sickness. But in all these and other contemporary contexts, health means life in its struggle against death, and sickness implies the menace of death. The idea that all sickness is potentially unto death, and that sickness unto death should be interfered with by the doctor are both of recent origin; they can be understood only if the parallel development of the death image becomes equally clear.

In every society the image of death is a culturally conditioned anticipation of uncertain date. This anticipation determines a series of behavioral norms during life and the structure of certain institutions.9 Insofar as death is a lifelong anticipation, the anthropologist or the literary critic can describe the death image of a society, the sociologist can study the different forms under which it spreads to age-groups and classes, the psychologist can investigate the personal progress of each member through this pre-existing cultural reality.10 All of them will be able to tell us something about how a society's image of death relates to its image of health. At least they will be able to tell us if ill health, pain or abnormality arc rarely, never, or usually seen as having a causal relationship to ensuing death.11

The Western cultural ideal of natural death is of quite recent origin. In 500 years it has evolved through four stages and is now ready for another mutation. A study of this history is the necessary groundwork for any authoritative analysis of the present crisis.

I will deal with the stages under the headings of (1) the skeleton man; (2) the timely death of the aging lecher; (3) death under the clinical eye; (4) union demands for natural death; and (5) death under intensive care. I will show that in each of the first four stages a new social ideal about the end of life called forth a new form of medical activity. In each stage the demands on medical performance preceded the demonstrated ability of medical practitioners to produce the results expected of them.

The Evolution of the Dance of Death

During the high Middle Ages, it was not Death but Hell which kept people in fear.12 In the morality plays of the declining Middle Ages, however, a new kind of Death appears. He is no longer the Apocalyptic rider of the Gothic and Roman reliefs, or the bat-like Maegera who picks up souls in the Cemetery of Pisa. He is no longer a messenger or angel sent by God, but a very personal figure who calls each man and woman and insists on his own rights.13

In 1404, the Duke de Berry had the first Dance of Death painted on the Wall of the Cemetery of the Innocents at Paris. King, peasant, and pope is each beckoned to dance with a corpse. The corpse reflects his features and his dre^ss. Everyman carries his own death with him in the shape of his body. Until this period, man had been accustomed to choosing between angel and devil who struggle for his escaping soul. Now, he sees himself in the mirror as his own lifelong memento mori. It is not Death, but rather his own dead self with whom he dances through the autumn of the Middle Ages. Life in front of the Mirror of Death (Chastellain) acquires hallucinating poignancy. During the age of Chaucer and Villon, Death becomes as sensual and as intimate as pleasure.14

By 1538, Hans Holbein the Younger published the first best selling picture book, his woodcuts on the Dance Macabre.15 The mystically intimate death flavored by the Devotio Moderna was here replaced by an egalitarian natural force: from an encounter with the mirror image, the Dance of Death turned into frenzied exhaustion in the grip of anonymous nature. The dance partner has shed its putrid flesh and turned into a naked skeleton. The representation of each man entwined with his own death has turned into a natural force dragging all into the whirl and then mowing them down. Death held the hourglass or struck the tower clock. The new machine which could make time of equal length, day and night, now struck the hour for all. Survival in any form had ceased to be a demand of nature, and—in the theology of the Reformation era—had become a frightful punishment or an unmerited gift from God.16 During the fifteenth century, death had become the true end, equally so for all.17 It had become more certain than immortality, more just than King or Pope or God, and the end of life rather than life’s aim.18 During the early sixteenth century, by becoming a force of nature, it cleared the way for reform and revolution of a new kind.

Once death had become a natural force, man wanted to master it by learning the art of dying. The instruction manual under the name of Ars Moriendi stayed on the best seller list during the next 200 years.19 Medicinal folkways designed to help people meet their death multiplied.20 People tried to learn how to face death, how to case it, how to detach themselves from all bonds which would make it difficult to observe its command. Remedies against a difficult death proliferated. Pilgrimage centers flourished where the sick could consult oracles to determine if they should seek remedies or if the time had come to be ready for death. The dying man played a new role which had to be played very consciously. His children could help him to die, but only if they did not hold him back by crying. He was placed on the ground, and prayers were said; but people were not to look at him, so as not to frighten death away. The medical writers of the sixteenth century recognized clearly the two opposed services they could provide: health or a speedy death. In both cases, the doctor was anxious to assist nature. Reformed health generated its own ritual in support of the myth, and this ritual kept the doctor away from the deathbed of the peasant until late into the nineteenth century.

This ambiguous attitude towards death comes out very clearly in the writings of Paracelsus.21 One recognizes him as one of the new doctors. “Nature knows the boundaries of its course. According to her own appointed term, she confers upon each of its creatures its proper life span, so that its energies are consumed during the time that elapses between the moment of its birth and its predestined end.” Death is a natural phenomenon: “What dies naturally has reached its appointed term, therein lies God’s will and order. Even if death occurs through accident or illness, no reawakening is possible. Therefore, there is no defense against the predestined end. Nature, too, is full of anxiety; she has recourse to everything that God has given her in order to repel death;” and this death is final:

She tries to drive out harsh, bitter death, who fights against her; dreadful death, whom our eyes cannot see, nor our hands clutch. But nature sees, touches and knows him. Therefore she summons all her powers of heaven and earth to resist the terrible one. A man’s death is nothing but the end of his daily work, an expiration of air, the consummation of his own balsamic curative power, the extinction of the rational light of nature, and a great separation of the three—body, soul, and spirit—a return to the womb.

Death for Paracelsus has become a natural phenomenon, without excluding belief in transcendence.

The new concern with the art of dying helped to reduce the human body to a kind of object, which could be used to advance the art of healing. Throughout the Middle Ages, the human body has been sacred and its dissection was considered by humanist Gerson “a sacrilegious profanation, a useless cruelty exercised by the living against the Dead.” This attitude still survives when modern law speaks about the “profanation” of graves, or of the “secularization” of a nondenominational cemetery which pre-ceeds its transformation into a park.22

When the corpse appears in the mystery plays, it also moves into the arena of the amphitheater of universities. The first publicly authorized dissection took place in Montpellier in 1375. It was afterwards declared obscene and the performance could not be repeated for several years. Later, one corpse per year was authorized for dissection within the borders of the German Empire. One also was dissected each year just before Christmas at the University of Bologna, and the ceremony took three days. The University of Lerida in Spain was entitled to the corpse of one criminal once every three years, to be dissected in the presence of a Notary assigned by the Inquisition. In England, in 1540, the faculties were authorized to claim four corpses a year from the hangman. But attitudes changed fast during the sixteenth century. By 1561, the Venetian Senate told the hangman to follow the instruction of Dr. Fallopius in order to provide him with corpses well suited for “anatomizing.” Another sixty years later, public dissection was a favored subject for Flemish painters, the best known work probably being “Dr. Tulp’s Lesson” by Rembrandt. At the same time, public dissections appeared as part of carnival programs.

The decay of the body had acquired a new finality. The heightened anguish was exorcized by a host of rituals surrounding the act of dying, by a new curiosity about the dead body, and by the production of phantasmic horror stories about the afterlife of the dead. The seventeenth-century’s grotesque concern with ghosts and souls underlines the growing anxiety of man facing the empty grave. What people did to preserve their health or to cure their ills had little to do with what they did when they felt threatened by death. Medicine was ancillary to Nature, helping it to heal, or helping man to die.

The Rise of the Aging Lecher

By the early eighteenth century, the image of death which cuts all people to equal size had spread wide and far. It had been exported from Europe by missionaries of otherwise opposed sects and could be seen in every parish. The Dance of Death might still be painted on a wall of the village cemetery, showing the Duke holding the shepherd’s knuckles, but the baroque Last Judgment painted on the opposite wall would have separate compartments in heaven and hell for kings, for virgins, and for commoners. The same prayers were still said and the same superstitions observed and the same remedies given at the bedside of the rich and the poor, even though the rich now played the ritual much more pompously and their funerals became an occasion for public parades. During the third quarter of the eighteenth century, this equality ceased. Bacon had already begun to speak about a new task of medicine, the task of keeping death away. He divided “medicine into three parts or offices; first the preservation of health, second the cure of disease, and third the prolongation of life.” He extolled the “third part of medicine regarding the prolongation of life: this is a new part, and deficient, although the most noble of all.” But while a few doctors might believe in this new vocation, for 150 years after Bacon, for rich and poor alike, “death is the grand leveller.” It is a “deadly disease neither physician nor physic can cure,” for “while old men go to death, death comes to young men.”

But then, during the 1760's, men became unequal in death. The reason for this was the rise of a new type of old man who refused to die in retirement and demanded to meet his death from natural exhaustion while on the job. It was not simply death in old age, but death in an active old age which he demanded—the old preacher expecting to go to heaven and the old philosopher denying the soul —both could agree now that natural death was only that death which overtook them at their desk. Where in the Middle Ages the same call from God came to sinners and saints, and in the Renaissance Nature brought the same end for all, in the seventeenth century death starts to come differently to different classes, it comes “timely” only for an elite.

The idea that natural death had to come in old age appeared, however, much earlier. Montaigne, in 1580, had ridiculed it: to die of old age is a death rare, extraordinary, and singular, and therefore so much less natural than the others:

’tis the last and extremest sort of dying.. . what an idle conceit is it to expect to die of a decay of strength which is the effect of extremest age, and to propose to ourselves no shorter lease on life... as if it were contrary to nature to see a man break his neck with a fall, be drowned in shipwreck, be snatched away with pleurisy or the plague... we ought to call natural death that which is general, common and universal.

But though the dream is old, the ability to transform it into a cultural pattern begins to emerge about 1730. Technological changes by this time have greatly changed life.23 The pampered rich could survive longer because living conditions had changed. Even more decisive was the change in working conditions. Sedentary work, hitherto rare, had come into its own. Also by this time, roads had improved: a general affected by the gout could command a battle from his wagon, and decrepit diplomats could travel through Europe. Office work multiplied and created the demand for a bourgeoisie. Rising entrepreneurship and capitalism favored the boss who had the time to accumulate capital or experience. The new class of old men survived because their lives at home, on the street, and on the job had become less extenuating. They refused to retire because an expanding bureaucracy favored the ageless who had been around for a long time. Aging became a way of capitalizing life.24

To keep them out of the way and simultaneously prepare them for economically valuable lives, the young were put into schools while the old stayed on the job. With their economic status, the value of the old man’s bodily functions also increased. In the sixteenth century a “young wyfe is death to an old man”; and in the seventeenth century “old men who play with young maids embrace death.” This changes in the course of the eighteenth century: the old lecher, who had been a laughing stock under Louis XIV, was envied at the Congress of Vienna. The patriarch appears as a literary ideal. Wisdom is attributed to him, just because of his age. It first becomes tolerable and then appropriate that the elderly rich should attend with solicitude to the rituals deemed necessary to maintain their ailing bodies. The physician whom they needed did not exist, since he was neither the traveling quack, Jew, or herbalist. Nor was he the resident barber or surgeon who knew how to let blood and set bones.

Formerly, only kings and poets had been under the obligation to remain in command to the day of their death. They alone had recourse to the great doctors from the universities, the Arabs of the Middle Ages from Salerno, the Renaissance men from Padua or Montpellier. To do what barbers did for the commoner, kings kept court physicians. Now the aging bourgeois believed himself burdened by the duty of aging on the job. The aging bureaucrat wanted to be cured from what his grandfather or his maid still accepted as a call to get ready for death. He was out to confuse what until then had been separate: on the one hand, he wanted to identify retirement with death; on the other hand, all ailments which struck him threatened to be sickness unto death. He wanted a doctor to drive away death, who also could give dignity to his new role of valetudinarian. He was willing to pay his doctor as nobody had payed before, because bourgeois death was conceived as the absolute price for the absolute economic value. The rationale for the economic power of the contemporary physician was thereby created.25

The ability to survive longer, the refusal to retire and the demand for medical assistance for incurable illness had joined to create a new definition of sickness: the type of health to which old age could aspire. Since this was the health of the rich and the powerful, malady soon became fashionable for the young and pretentious. Protracted ailments in preparation for natural death became a sign of distinction. The poor were condemned to die of untreated ills, which all lead to untimely and therefore unnatural death. It fitted the image one had of the proletarian; he was also uneducated and unproductive. Earlier, death had carried the hour glass. If the victim refused, both the skeleton and the onlooker grinned. Now society takes the watch and tells death when he may decently strike. Health has become the privilege of waiting for a natural death. In the next epoch, it becomes the ability to die with the rituals of medical ministration.

The Opening of the Clinical Eye

Two generations later it became highly respectable to live as the client of a famous doctor. Four generations later, industrial workers demanded the right to medical and retirement insurance. The valetudinarian’s image of timely extinction at the end of a pampered life first mutated towards the solicitude of all ages to oppose death from a clinically defined sickness, and then to the claim by the unions to medical and old-age insurance against unnatural death. In barely a hundred years, the concept of natural death thus went through two distinct evolutions and in the process changed the ideas both of health and of social justice.

At first, untimely death got clinical names. Attention shifted from the sick to his sickness, from his being sick to his having a sickness.26 Sickness became an entity or problem, and therapy, a procedure or solution which was effective if applied by the doctor. Once sickness could be treated by the doctor rather than letting nature assist in the person of the ailing man’s own body (Paracelsus), medicine had moved into the industrial age. The relationship of the healer to the suffering man was now superceded by that of the medical institution to the patient. Man who must heal or die is substituted by the image of man the consumer. He functions as long as he gets therapy and health. Untimely death turns into underconsumption of clinical care, which can be explained by backwardness of medical science, self-seeking doctors, or unjust social arrangements. The stage is set for the idea of unnatural death as a result of under-consumption.

The first important step towards clinical production was taken by making hospitals out of eighteenth-century pesthouses, homes for the incurable, bedlams, and orphanages. Hospitals become industrial institutions for the mass-production of health services, repairshops for people. This establishment resulted from the idea of the same generation which discovered that defectives of every sort had to be locked up among their like if they were to be bettered: in schools to be given education, in prisons to be given correction, and in hospitals to be returned to health. Only such institutional mass-production of services fits two key illusions of the industrial revolution: “better” satisfaction of man’s needs by rational production, and the satisfaction of more needs for more people.

While the city doctor became a clinician, the country doctor became sedentary. It is important to remember that at the time of the French Revolution, he still belonged among the traveling folk. The surplus of army surgeons from the Napoleonic wars, all of them trained on the job, had to earn a living. They settled in villages and became the first class of resident healers. The simple people did not trust their new techniques, and the sedentary burghers were shocked by their rough ways. Their sons, around 1830, created the role of the country doctor which remained unchanged until the Second World War. His stable income was derived from the demands placed on him by the few middle class valetudinarians. He still had to compete with the medical technicians of old: the midwife, the dentist, the veterinarian, the barber, and sometimes the nurse. But within a generation, he could establish himself as a member of the solid middle class. The demand for his health services was sufficient both to provide him income and to send the sick to his clinical colleagues in town.The attempt to provide a natural death by referral through a hierarchy had begun.

Timely death under treatment of clinical symptoms emerged as the ideal of the middle class and its doctors.27 Natural death during the first half of the nineteenth century was class-specific.

Union Claims for Equal Death

Then death became a union demand. The valetudinarian’s health concept was written into labor contracts. The privilege of natural extinction from active old life in business was replaced by the mass demand for such a death for the pensioner.28 The bourgeois image of the dirty old man still at his desk was replaced by the proletarian image of a healthy sex life on social security. The ideal of ending life on the job turned into the right to start life after retirement from it. The condition for the right of this proletarian form of natural death was lifelong clinical care for every clinical condition.29 This vindication for health care was soon incorporated into political rhetoric and legal definitions. Natural death and the health-care preparation for it was something which society owed its members. The death concept entered into social justice.30 The right was formulated as a claim to equal consumption of social products rather than as a freedom from torts or new liberty for self-care. Just as, at this time, all men were defined as pupils, born in original stupidity and standing in need of several years of schooling before they could enter life, so they were defined as born patients who needed many kinds of treatment before they could leave life. Man now cannot take his place in the world before he has proven educational consumption and he cannot exit from the world without having been forced through medical programs. Just as compulsory educational consumption became a device to rationalize discrimination on the job, so compulsory medical consumption became a device for the rationalization of unhealthy work, cities, transportation, play, etc.

The redefinition of workers as health consumers had a double effect. At first it showed a revolutionary potential but soon it became a means for social control.31

At the turn of the century, the euphoria over medicine’s ability to ban untimely death provided ammunition to social critics. Every death without medical assistance was labeled untimely, and denounced as a scandal for whch a culprit had to be found. Of course, natural death was to be explained by a natural cause. It would not do to accuse the evil eye of the enemy, the evil intention of the magician, or the arbitrariness of a god. The culprit had to be found within society: the class enemy, the exploiting doctor, or the colonial master. The witch hunt at the death of a tribal chief was modernized into the hunt for those responsible for social injustice. Without this revolutionary use of a death ideal, the progress of social legislation during the first half of the twentieth century could not have happened. Without it, social agitators could not have enlisted support for reforming laws nor mobilized the guilt feelings necessary to enforce their enactment.

Contemporary social organization cannot be fully understood unless it is also seen in the perspective of a multifaceted exorcism of all forms of evil death.32 Our major institutions constitute a gigantic defense program waged on behalf of “humanity and against unnatural deaths.33 Not only medical agencies, but also welfare, international relief, and development programs are enlisted in this struggle. Ideological bureaucracies of all colors join in the crusade. Even war has been justified to defeat those who are blamed for wanton tolerance of sickness and death.

The revolutionary potential of the unionized death image became exhausted as soon as it had been written into the charters of established institutions. The production of natural death for all men is at the point of becoming an ultimate justification for social control.34

Only the culture which has evolved in highly industrialized societies could possibly have called forth the commercialization of the death image I have just described. In its extreme form, natural death is that point at which the human organism refuses any further input of treatment—when man becomes useless both as producer and as consumer.35 It is the point at which a consumer trained at great expense must be written off as a total loss.36 It is the ultimate form of consumer resistance.

Within an industrial society, medical intervention into everyday life does not change the image of health and of death which prevails, but rather caters to it. It diffuses the death image of elites to the masses and reproduces it for future generations.37 But applied outside of a cultural context in which consumers prepare themselves religiously for a natural death, bio-medical engineering and modern medical practice inevitably constitute a form of imperialist intervention. They impose a compulsory socio-political image of death. People are deprived of their traditional vision of what constitutes health and death. The self-image which gives cohesion to their culture is dissolved, and atomized individuals can be incorporated into an international mass of health consumers.

I was taught what this means on the frontier of Upper Volta. I asked a man if people over the border, in Mali, spoke the same tongue. He said: “No, but we understand them, because they cut the prepuce of their boys as we do, and they die our kind of death.” Once a culture is deprived of its death, it loses its health. In the process of transition, people still have their way of knowing why and how death comes; but the modern doctor who comes to educate, claims to know better. He teaches them about a Pantheon of evil, clinical deaths, each one of which he will ban for a price. By his ministrations he urges them on the unending search for the good death of international description, a search which will keep them his clients forever.38

We have seen that in western society so far, medicine has served to legitimize changes which have taken place in a cultural context. In the last five centuries, the idea of death and the demand for a new kind of health have evolved one step ahead of the necessary techniques and rituals of health-care. We have seen that just the opposite happens when the latest type of health care is introduced into a traditional society. The introduction of new techniques, there, leads to the adoption of a new ritual; as a result, a new myth about death emerges which in turn redefines health in relation to death. Of course, this myth is usually hybrid, like the saints of Latin America. At Guadalupe, priests minister to the Mother of Jesus who has taken the shape of a Mediterranean Gea while the people worship her in the guise of Tonanzin, the earth mother of the stars, who gives birth to them each evening and swallows them in the morning, filling her belly with bones. But inevitably the hybrid myth about health which results from the implantation of Western medicine defines health as a struggle against death by escalating application of industrial power. The hybrid myth has its place in the industrial world.

Health care is now a monolithic world religion whose tenets are taught in compulsory schools and whose ethical rules are applied by a bureaucratic restructuring of the environment. The struggle against death which in another century dominated the thoughts and lives of the rich, has now become the rule by which the poor of the earth are forced to conduct themselves. In the strict sense used by religious sociologists, medicine has become the dogma around which the structuring ritual of our society is organized. Like any effective ritual, participation in medical practice hides from the producer and the consumer the contradiction between the myth which the ritual serves and the reality which this same ritual enforces and reproduces. Bio-medical intervention into the life of the individual, the group and the biosphere, comes to be seen as the condition for a natural death. Inquisitorial supervision of compulsory treatment and the planned reorganization of the environment according to the dictates of medical prejudices are advocated as a condition for a “natural” evil.39 Nature exorcised from a hygieni-cally planned life claims everyone—but only at his or her grave. The right to die of a natural death is turned into a duty on which teachers, doctors, politicians, and priests insist.40

Traditionally, the man best protected against death was he whom society had condemned to death. Society felt threatened that he could die without permission. Now the same authority is claimed over every citizen.41 What was a factual necessity in the late Middle Ages is now turned into a normative one. Natural death has become a distorted mirror image of the death represented in the dance macabre. It has resumed its egalitarian character; but while it was then a natural force which stopped man with the hourglass, it is now a chronometer out to stop death. Man, faced by death, was then asked to be aware that he was finally, frighteningly, totally alone; society now obligates him to seek medicine’s protection and let the doctor fight.42 Death has reacquired its pervasive threat. But where the skeleton man announced his coming by sickness unto death and each man’s dignity demanded that he recognize the signs, institutional medicine now impresses on each man and woman their duty to watch by constant checkups for any symptom that would require clinical defense. While the “Art of Dying” taught those of the Reformation era to face bitter death, to make ready and hope for a speedy end, compulsory treatments now eliminate all final agonies which might be easy but arc labeled unnecessary in order to preserve modern man for chronic disability or for cancer and decrepitude.43 While the dancing partner of the Middle Ages was symbolic of something which really waits for each man, natural extinction from old-age exhaustion is a lottery ticket for only a few.44

THE END

Illich would, I imagine, cringe at having heard me calling him a “theologian”. “I do not want to appear as a fundamentalist preacher or, worse, a Catholic theologian. I have not been given the official mission to teach Catholic theology.”—he said on occasion. Fair enough, Mr. Illich, fair enough.

Illich’s language is demanding and requires a certain suspension of judgement, I suppose, if one is to penetrate the systemic meaning behind his often challenging rhetoric. Reading Ivan Illich is not easy for me, but it has been worth the effort.

Cf. Rick J. Carlson, The End of Medicine (New York: John Wiley, in press). This is the clearest, most complete, and most readable summary of the arguments which explain the current institutional crisis in medicine.

Cf. Eliot Freidson, The Profession Of Medicine (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1971).

Cf. J. P. Dupuy, et al., “La Consommation de medicaments: Approche psycho-socio-economique” (Paris: CEREB, 1971, mimeographed.)

Cf. Elaine Adamson, “Critical Issues in the Use of Physician Associates and Assistants” (San Francisco: University of California, Division of Ambulatory and Community Medicine), mimeographed. This paper delineates a method to increase the production and delivery of health care by the use of paraprofessional levels in the medical hierarchy, and reviews the cultural obstacles to such a policy. See also Oscar Gish, Health, Manpower and the Medical Auxiliary (London: Intermediary Technology Development Group, 1971).

Academy of Parapsychology and Medicine, “The Varieties of Healing Experience,” (transcript of the Interdisciplinary Symposium, October 30, 1971).

Cf. Placidus Berger, “Religioeses Brauchtum ini Umkreis der Sterbeliturgie in Deutschland,” Zeitschr. Fur Missions und Religionswissenschaft, 48 (1964), 108-19, and 248.

Cf. Herman Feifel, “Attitudes Toward Death in Some Normal and Mentally Ill Populations,” in The Meaning of Death, ed. by Herman Feifel (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965), pp. 114-33. Cf. Robert Olson, “Death,” Encyclopedia of Philosophy, II, 307-09.

Cf. Renée C. Fox, Experiment Perilous (Glencoe, III.: Free Press, 1959) and “Illness,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (1968), VII, 90-95. She elaborates on the ideas of Talcott Parsons on the sick role. Cf. Robert Fulton, Death and Identity (New York: John Wiley, 1966), who has collected a broad spectrum of studies on the impact of the death-image on personal identity in modern societies. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross, On Death and Dying (New York: Macmillan, 1969), describes four typical attitudinal stages through which her Chicago patients pass before death and provides guidance to hospital personnel to enable them to lead the dying patient through these standard stages by using appropriate therapy. Orville Brim et al., The Dying Patient (New York: Russel Sage Foundation, 1970), deals first with the large range of professional analysis and decisions in which health professionals are believed to be involved in determining how and when an individual’s death should occur, and then with their recommendations about what might be done to make the process somewhat less graceless and less distasteful to the patient and his family. Robert Hertz, Death and the Right Hand (Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press, 1960), presents a dated but well-documented ethnological study on the universal belief in survival, principally among Malaya-Polynesians and their different forms of collective representation of death. This is still an essential work.

Cf. Stephen Polgar, “Health and Human Behavior,” Current Anthropology, 3 (April, 1962), 159-205. A review of the literature up to 1960 with comments by each of thirty-five other specialists in the field. Also cf. Marion Pearsall, Medical Behavioral Sciences (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1963). This is a more comprehensive bibliography which has a subject index, but is not annotated.

Cf. Alberto Teneti, Il senso della morte e I’amore della vita nel Rinascirnento (Turin: Einaudi, 1957), and cf. Berger, “Religiöses Brauchtum.”

Cf. J. Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages, Doubleday Anchor Books (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, n.d. [original publication, 1924]) on the evolution of the death image from the late thirteenth century to the early fifteenth century in poetry and art. See especially Chapter 11, “The Vision of Death,” pp. 138-51.

Cf. L. P. Kurtz, The Dance of Death and the Macabre Spirit in European Literature (New York: 1934, reprint Golden Press), for all of Europe and cf. Walther Rehm, Der Todesgedanke in der Deutschen von Mittelatte bis zur Romantik (1928, reprint Wissenschaft Buchgesellschaft), for Germany: Kurtz and Rehm provide detailed evidence from literature for my thesis of a major mutation in the death image around 1400 and again in 1520. See Johannes Kleinstueck, “Zur Auffassung des Todes im Mittelater,” Deutsche Vierteljahresschrift fur Literaturwiss enschaft und Geistesgeschichte 28 (1954), 41, who criticizes Rehm and claims more continuity. (The moralists had to make death hideous to insist on its importance and imminence; death was too much a part of life to attract any attention otherwise.) For iconography, cf. K. Kuenstle, Die Legende der 3 Lebenden und der 3 Toten (n.p., 1908), who is easier to consult than Male.

13 Cf. Hans Holbein the Younger, The Dance of Death: a Complete Facsimile of the Original 1538 French edition (New York: Dover, 1971).

Paul Landsberg, Essai sur I’experience de la mort (Paris: 1951). This is an important essay showing that the sense of finality and imminence of natural death can be considered the presupposition for a Christian view of the resurrection. Cf. G. B. Ladner, The Idea of Reform (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1959), especially p. 163 for the two currents within the church about death’s relation to nature since the fourth century. For Pelagius, death was not a punishment for sin, and Adam would have died even had he not sinned. In this, he differs from Augustine’s doctrine that Adam had been given immortality as a special gift from God, and even more from those Greek Church Fathers according to whom Adam had a spiritual, or “resurrectional” body, before he transgressed.

Jacques Choron, Modern Man and Mortality (New York: Macmillan, 1964), deals with the fear and the hope related to death in a number of select philosophers since Socrates. He relates the idea of final and necessary natural death to the emergence of individuality and a changed time concept. Note that Choron does not deal with popular attitudes towards death. Cf. Teneti, Il senso della morte, for Renaissance death. See Jacques Choron, Suicide (New York: Scribner’s, 1972), for changes in the attitudes towards suicide from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, especially pertaining to Erasmus and Sir Thomas More.

Death becomes the point at which linear clock-time ends, and eternity meets man, an eternity which during the Middle Ages had been (with God’s presence) immanent in history. Cf. H. Plessner, “Ueber die Beziehung der Zeit zum Tode,” Eranos Jahrbuch 5 (1951), 20. With the predominance of serial time, with concern for exact time-measurement and recognition of simultaneity of events, a new framework for the recognition of personal identity is constructed. The person’s identity is sought in reference to a sequence of events rather than in the completeness of his life-span. Death ceases to be the end of a whole and becomes an interruption in the sequence. Cf. Alois Hahn, Einstellung zum Tod und ihre Soziale Bedingtheit (Stuttgart, 1968), on the effects which a change in time-perception had on the perception of death.

For bibliography on the Ars Moriendi, see Mary Catherine O’Connor, The Art of Dying (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942, reprint New York: Abraham Magazine Service, 1967).

These customs live on. Cf. Arnold van Gennep, Manuel de folklore français contemporain, Vol. I, part 2, for the preparation for death in France and on procedures which are believed to ease death. See especially p. 649: La mort comme phénomène contagieux la mort personnifiée, les neuf présages de la mort, procèdes pour hater F agonie, arrêt de l’horlage, etc . . . See Lenz Kriss Rettenbêck, Bilder und Zeichen Religioesen Volksglaubens (Munich: George Calloway, 1963), for the extraordinary riches of plastic fold-art related to death which combines the sense of finality, necessity and horror of the grave with deep Catholic belief in salvation. This is a masterly study of mostly Bavarian folk-art.

Paracelsus, ed. by J. Jacobi (Bollinger Ser., 1958), is an excellent, easily readable introduction to his thought.

The transformation of the corpse into a thing that can be used for the advancement of science happens at this time. For a while, the corpse still has to be protected as a quasiperson. Cf. Paul Fischer, Strafen und Sicher-nede Massnahmen gegen Tote im Germanischen und Deutschen Recht (Düsseldorf, 1936), for the history of punishments meted out to the dead. Remember that various religions still accord or refuse “rights” to the dead. See Paul Julien Doll, “Les Droits de la science apres la mort,” Diogene 75 (July, 1971), on the survival of medieval traditions about the human body in contemporary law. Cf. Hans Hentig, Vom Ursprung der Henkersmahlzeit (Tubingen, 1958) on the widespread psychological attraction of the dead body.

Philippe Ariès, Histoire des populations françaises: et de leurs attitudes devant la vie depuis le XVIIIe Siecle (Paris: Seuil, 1971 [originally 1946]). His chapter, “Les Techniques de la mort,’’ pp. 373-88 contains a rich summary of information about the changing attitudes of different levels of the French population towards death during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For those who know the author’s Centuries of Childhood, it is especially interesting to observe that precisely those social classes which can afford to eliminate “social death” by means of traditional retirement create “childhood” as an institution for their children.

Cf. Simone de Beauvoir, The Coming of Age (New York: G. P. Putnam’s, 1972). See “Old Age in Historical Societies” for much illustration on new types of old age in different layers of society during the sixteenth through eighteenth centuries.

Theodor Adorno, Minima, Moralia, Reflektionen aus dem deschaedigten Leben (Frankfort, 1962).

Michel Foucault, The Birth of the Clinic (New York: Pantheon, 1973) points out that sickness conceived against the backdrop of death ceases to be a negative entity, a disturbance of life which can never be fully ceased or defined, and becomes clearly definable and distinctly visible to the clinical eye. Sickness ceases to be a lack of health and acquires a body within the ailing body of the individual.

Richard A. Kalish, “Death and Dying, a briefly Annotated Bibliography,” in Death and Dying, ed. by Brim et al., for a selected bibliography of English language literature on Death and Dying in a modern setting. It includes social science, medical and hospital administration items. Cf. John W. Riley, “Death,” International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (1968) IV, 19-25, for survey of social science literature trends in the United States in the study of death and bereavement. Cf. Robert W. Haberstein, ibid., p. 26-8, for a short survey of contemporary American studies on the social organization of death.

Werner Fuchs, Todesbilder in der Modernen Gesellschaft (Suhrkamp, 1969). Fuchs uses the content-analysis of obituaries as a means of ascertaining contemporary images of death. But he also suggests the use of dictionaries for this purpose. One of the major German encyclopedias of 1909 defines abnormal death as that which “is opposed to natural death because it results from sickness, violence, or mechanical and chronical disturbances.” A very generally accepted dictionary of philosophical concepts defines natural death as that “which comes without previous sickness, without definable specific cause.”

Unions now seem to have travelled in a full circle. Daniel Maguire, “Freedom to Die,” Commonweal (August 11, 1972), 423-7, suggests that by working creatively and in ways yet unthought of, the lobby of the dying and of the gravely ill could become a healing force in society. It could reconquer the “Freedom to Die.”

Just as universal education by means of compulsory schooling cannot promote equality but must favor those who start earlier, are healthier, and have greater learning opportunities at home, so equal opportunities for a timely death by means of free medical services can only raise the relative advantage of those who do not need these. The human cost of artificial prolongation of decrepitude inevitably weighs heavier on the poor than on the rich. Medical assistance was more effective in providing for the poor access to death from kinds of sickness which so far had been the privilege of the rich (old age and civilization sickness) than it was in helping the masses to end their lives in that kind of active and creative old age which the rich had claimed for themselves in the nineteenth century.

Fuchs, Todesbilder in Gcsellscaft, is the source for many of the ideas and the guide to some of the literature in this essay. The author tries to unmask the thesis about the repression of death in modern societies which he finds unfounded and instrumental. According to the author it is usually promoted by people of profoundly anti-industrial persuasions for the purpose of demonstrating the ultimate powerlessness of the industrial enterprise in face of death. It is usually insisted upon to construct apologetical arguments in favor of the need for belief in God or afterlife. The fact that people have to die is taken as proof that they will never autonomously control reality. He interprets all theories which deny the finality of death as relics of a primitive past and considers as scientific and now tenable only those corresponding to a modern social structure. The death image of a society is a dependent variable in relation to it. He analyzes the contemporary image of death, principally by studying the language used in German obituaries. He believes that what is usually called “repression” of death is due to a lack of effective acceptance of the increasingly more generally accepted reality of death as an unquestionable and final end.

Guenther Anders, Endzeit und Zeitendende: Gedanken uber die atoniare Situation, (n.p., 1972). Not only the image of personal death is new. The image of the end of the world has also changed. Death is the end of my world. But each society has to live with an attitude towards the end of the world. The atomic situation has deeply affected attitudes about the Apocalypse. Rather than a mythological expectation it is a real contingency. Rather than being due to man’s guilt, it is a possible consequence of man’s direct decision. There is an uncanny analogy between atomic bombs and cobalt bombs: both deemed necessary for the good of mankind, both effective to provide man with the power to decide when the end shall come, and thereby strengthening the illusion that, by the proper use of these tools, it will come in a more natural way. See also, Robert J. Lifton, Death in Life: Survivors of Hiroshima (New York: Random House, 1968). See K. Jaspers, Die Atombombe mid die Zukunft des Menschen (DTV, 1961).

Bronislaw Malinowski, Magic, Science and Religion, introd, by Robert Redfield, Doubleday Anchor Books (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, n.d. [1948]), p. 53. Malinowski argues that death among primitive people threatened the cohesion and survival of the group by leading to an explosion of fear of death and irrational expression of defences. Group solidarity is saved by making out of the natural event, a social ritual. Death becomes then an occasion for exceptional celebration of tribal or group unity. It might be argued that in an impersonal and industrial ritual, modern medicine celebrates the unity of mankind in their relatedness to an identical ideal death, and thereby diminishes the guilt and anxiety about the evidently different kinds of death that people die, who find their place on different levels of the medical consumer pyramid.

William Ophuls, “Leviathan or Oblivion” (Cuernavaca: CIDOC, 1972), Limites no. 1, pp. 1-25. A provisional manuscript for a chapter in a learned and well-documented thesis within the context of which this issue could be well-discussed.

Cf. Edgar Morin, L’Homme et la mort (Seuil, 1970), for whom the contradictions of bourgeois individualism are corroborated by man’s inadaptation to any possible form of realistic death where the current industrial ideology prevails.

Cf. Thomas Szasz, “Malingering: ‘Diagnosis’ or Social Condemnation? Analysis of the Meaning of ‘Diagnosis’ in the Light of Some Interrelations of Social Structure, Value Judgment, and the Physician’s Role,” Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry (A.M.A.) 76 (1956), 432. Szasz insists that the ritual of medicine takes, like other rituals of contemporary society, the form of a game. Therefore, the physician’s chief function is that of an umpire: “he is the agent or representative of the social body (the game) and it is his duty to make sure that everyone plays the game according to the rules.” The rules, of course, forbid leaving the game and dying except in carefully specified settings. Richard M. Bailey, “Economic and Social Costs of Death,” in The Dying Patient, pp. 275-302, from an economic, analytical point of view, tries to specify how economics should attempt to measure the economic costs of death and the value of life. He argues that we cannot avoid placing dollar value on life, so let us do it explicitly. A new rationalization of the entire health-care system will result from cost-benefit analysis of terminal treatment.

Various ideological bureaucracies lend important support to the double image of natural death. It would be interesting to study at least one in depth. For this purpose I would recommend research on Christian support for the Janus-faced modern death. See André Godin, “Has Death Changed?” Death and Presence: the Psychology of Death and the Afterlife, ed. by André Godin, in Studies in the Psychology of Religion, translated from French (Brussels: Lumen Vitae, 1972). Godin could provide a good starting point. This anthology contains a number of sociological and psychological studies concerned with a Christian education on (for?) death. Several studies highlight the greater anxiety and conflict of religious studies in the face of death. Pierre Delooz, “Who Believes in the Hereafter?” in Godin, Death and Presence, 1972, suggests that contemporary French-speakers have effectively separated belief in God from belief in the thereafter. P. Danblon, “How Do People Speak About Death?” in Godin, Death and Presence, 1972, studies the structured interviews of 60 French-speaking public figures. It would appear that cross-denominational analogies in their mode of expression, feelings and attitudes towards death are stronger than differences due to varying beliefs. Godin reviews studies on the changing image of death in our generation, and their relevance to Christian education and chaplaincy. None of these studies explicitly deal with medicine as a mythopoetic ritual engendering the tolerance for a contradiction between the reality which sick persons experience and the ideal which society pursues. They do not, therefore, deal directly with the crisis which arises from the simultaneous acceptance by a person of a Christian death and resurrection-oriented belief and the person’s participation in the ritual of medicine which promises to banish death and suffering.

F. N. L. Poynter, ed., Medicine and Culture, (London: Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine, 1969).

David Sudnow, “Dying in a Public Hospital.” in Brim et al.. The Dying Patient. Sudnow describes how death becomes a selffulfilling prophecy of the medical ritual and lists three stages of social death which precede the wrapping of the body by orderlies. A sober and hallucinating well-illustrated summary of observations in U.S. Public hospitals. See also Avery Weisman, On Dying and Denying: Psychiatric Study of Terminality (New York: Behavioral Publications, 1972), on the discrepancy between the wish of people to die in dignity and the actual services that they purchase.

Joseph Fletcher, “Anti-Dysthanasia: the Problem of Prolonging Death,” Journal of Pastoral Care 18 (1964), 77-84. In an article against irresponsible life-prolongation, written from the point of view of a hospital chaplain, he argues: “I would myself agree with Pope Pius XII and with at least two Archbishops of Canterbury, Land and Fisher, who have addressed themselves to this question, that the doctor’s technical knowledge, his ‘educated guesses,’ and experience, should be the basis for deciding the question as to whether there is any ‘reasonable hope.’ That determination is outside a layman’s competence.... But having determined that a condition is hopeless, I cannot agree that it is either prudent or fair to physicians as a fraternity to saddle them with the onus of alone deciding whether to let the patient go.” This thesis is common, and shows how even churches support professional judgment.

According to Hentig, Ursprung der Henkersmahlzeit, 1958, ritual murder is not limited to judicial execution, but wherever it is performed, a meal for the condemned man (sometimes today reduced to a last cigarette) precedes the ceremony, and a meal (breakfast of the witnesses) usually follows. The author assembles information from all countries and epochs. He points out that only the soldier of modern times is trained to kill rather than for fighting and might be the first professional executioner not providing his victim with ritual notice by means of a meal. Note that the modern doctor is also the first professional healer who does not act as nuntius mortis when the appropriate time has come.

“L’homme du second Moyen Age et de la Renaissance (par opposition a l’homme de premier Moyen Age, de Roland, qui se survit chez les paysans de Tolstoi) tenait à participer à sa propre mort, parce qu’il voyait dans cette mort un moment exceptionnel où son individualité recevait sa forme definitive. Il n’était le maître de sa vie que dans la mesure ou il était le maître de sa mort. ... à partir du XVII siècle il a cessé d’exercer seul sa souveraineté sur sa propre vie, et par conséquent, sur sa mort. Il i’apartagée avec sa familee. Auparavant, sa famille était ecartée des decisions graves qu’il devait prendre en vue de la mort, et qu’il prenait seul.” Philippe Ariès, “La Mort Inversée: Le changement des attitudes devant la mort dans les sociétés occidentales,” Archives Européenes de Sociologie 8 (1967), 175.

The Ars Moriendi charges the spiritual, as opposed to the “carnal” friend with the task of acting as nuntius mortis and of reminding the friend of approaching death. The more we rise in the social ladder through the eighteenth century, the less people perceive that death approaches; in the middle of the eighteenth century, the physician ceases to act as nuntius mortis. During the nineteenth century, he speaks only when pressed. Telling a person that death is near in some regions is a task taken over by the family, but only in the nineteenth century. The dying man ceases to preside over the ceremonial of his own death, and the doctor transforms it into the last stage of therapeutic pretensions. The death-chamber loses its candles, closed drapes, family reunions, and veracity, and becomes a hygenic, lonely, and professional environment for deception about the imminent.

Other works which were consulted in the preparation of this paper and may be of interest to the reader include:

A. Alvarez, The Savage God (New York: Random House, 1970); Werner Bloch, Der Arst und der Tod in Bildern aus sechs Jahrhunderten (Stuttgart: 1966); Ladislaus Boros, The Mystery of Death (New York: Herder and Herder, 1965); R. Broca, Cinquante Ans de conquêtes médicales (Paris: Hachette, 1955); Harley L. Browning, “Timing Our Lives,” Transaction, October, 1969, 22-7. G. Buchheit, Totentanz (1938); Eric J. Cassell, “Treating the Dying: the Doctor vs. the Man within the Doctor,” Medical Dimension, March, 1972, 6-11; E. Codman, “The Product of the Hospital,” Surgery, Gynocology and Obstetrics 18 (1914), 491-6; P. Delauney, La Vie médicale aux XVE, XVIE, XVHE siècles (Paris: 1935); Thomas M. Dunaye, “Health Planning: A Bibliography of Basic Readings” (Council of Planning Librarians, 1968; mimeographed); E. Doering-Hirsch, Jenseits im Spaetmittelalter (Berlin, 1927); José Echeverria, Réflexions métaphysiques sur la mort et le problème du sujet (Vrin: 1957); R. Ehlund, “Life between Death and Resurrection according to Islam,” (Uppsala, Sweden: 1941; dissertation); Gabriel Fallopius, Observa-tiones anatomicae (Venice, 1561); H. Fehr, “Tod und Teufel in Alten Recht,” Zeitschr. der Savignystiftung fur Rechtsgeschichte 67 (1950?), 50-75; Christian von Ferber, “Sociologische Aspekte des Todes: Ein Versuch uber einige Beziehungen der Soziologie zur Philosophischen Anthropologie,” Zeitschr. Fur Evangelische Ethik 7 (1963) 338-60; Albert Freybe, Das Momento Mori in Deutscher Sitte, Bildlicher Darstellung und im Volksglauben (1911); and Das alte Deutsche Leichenmahl in Seiner Art und Entartung (1909); H. Friedel, “L’Experience humaine de la mort,” Foi et Vie 63, 105-17; Stanley Brice Frost, “The Memorial of the Childless Man: A Study in Hebrew Thought on Immortality” (Winnipeg: paper read to Canadian Biblical Society, Winnipeg, 1970); V. E. Frh. von Gebsattel, Prolegomena einer Medizinischen Anthropologie (Berlin: 1954); Siegfried Giedion, Mechanization Takes Command (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1948); Oscar Gish, Health, Manpower and the Medical Auxiliary (London: Intermediary Technology Development Group, 1971); Romano Guardini, The Death of Socrates, Meridian (New York: World Publishing, 1970); A. Guehring, De Todes—Auffassung der Deutschen Volks-Sage (Tubingen, 1956; dissertation); Pastor E. Heider, “Aus-druecke für Tod und Sterben in der Samoanischen Sprache,” Zeitschr. Für Eingeborenensprachen 9 (1919), 66-88; Edgar Herzog, Psyche and Death (New York: G. P. Putnam’s, 1967); Hans Jonas, “Technology and Responsibility: Reflections on the New Task of Ethics,” Social Research 40 (1973), 31-54; John Koty, Die Behandlung der Alten und Kranken bei den Naturvoelkern (Stuttgart, 1934); Claude Levi-Strauss, The Savage Mind, Phoenix Series (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969); John T. Marcus, “DeathConsciousness and Civilization,” Social Research 35 (1964), 265-79; Karl Rahner, On the Theology of Death (New York: Herder and Herder, 1963); Jonas Robitscher, “The Right to Die: Do We Have the Right not to Be Treated?” Hastings Center Report [4] (1972); R. Shyrock, The Development of Modern Medicine (New York: Knopf, 1947); Charles Wahl, “The Fear of Death,” Death and Identity, ed. by Robert Fulton (New York: Wiley, 1966).

Further reading (and viewing), in random order, recommended by “The Flying Fish”:

“The Corruption of the Best: On Ivan Illich”, by Geoff Shullenberger, here.

The fifth chapter from Illich’s Medical Nemesis, (1976), here

“Death Undefeated: From Medicine to Medicalisation to Systematisation”, (1995), by Ivan Illich, here

Life is a Test: Ivan Illich’s Medical Nemesis and the “Age of the Show” on YouTube, here. The video clip features Babette Babich, a philosophy professor at Fordham University, offering an intriguing viewpoint on the concepts put forth by Illich in his Medical Nemesis. This talk is an adaptation of a talk she gave in August 2016 in Quebec, Canada to the International Philosophy of Nursing Society. Professor Babich offers a wry reflection on the current state of medicine and its “cutting edge” aspects forty years after the publication of Medical Nemesis.

“Reading Ivan Illich on the Elemental Body”, (2023), an essay by Prof. Babette Babich here

“Death as an unnatural process: Why is it wrong to seek a cure for ageing?”, by Arthur L. Caplan, here

“Between Hope and Acceptance: The Medicalisation of Dying”, by David Clark, here

“The history of natural death is the history of medicalisation of the struggle against death”, Ivan Illich, 1976, here

“Questions About the Current Pandemic From the Point of View of Ivan Illich”, by David Cayley, April 2020, here

The possibility of a podcast, with Michel Houellebecq

The French author Michel Houellebecq, much admired by The Flying Fish, affirmed recently that a civilization that legalizes euthanasia loses all respect. (I agree.) A few months ago, Monsieur Houellebecq was the guest of Anna Khachiyan and Dasha Nekrasova