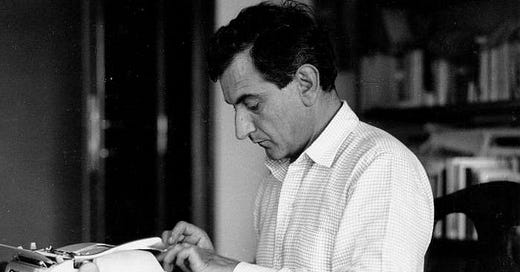

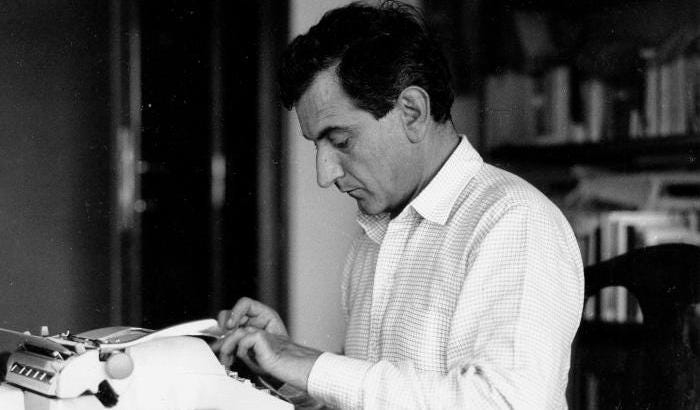

Goffredo Parise: “The Remedy is Poverty”

A piece of critical intelligence and absolute clarity, to be read and re-read in order to better live in this society that distracts us from the essential. (A 5-minute read.)

A small introduction

As you, the present Reader, might have noticed, from time to time I enjoy posting in “The Flying Fish” those little masterful gems of thought, those that are written by others. I am too much of an ignoramus (genuinely) to come up with gems myself, but I do have my moments: I recognise splendour when I see it.

Recently, I have found Parise.

Goffredo Parise (Vicenza 1929-Treviso 1986)1, to me, is a writer among those who are spokesmen and spokeswomen for my own perception and critique earthly life, while being free and removed from all political and ideological affiliations just as I would claim to be.

Without the pretense of wanting to be a master, Parise is sure to “spank” me a little when I’m reading him—spanking which at times feels like a reprimand of a stern grandfather trying to open the eyes of his grandson—exhibiting the great desire to make me, his reader, a mature, thinking person. I already have an affinity for those non-master-like masters of spank (e.g. Ivan Illich, Blaise Pascal, Karl Kraus, or Giacomo Leopardi). Now, Goffredo Parise has been added to the my precious posse.

I did not know of Parise before reading his «Il rimedio è la povertà» (The Remedy Is Poverty), the small essay which an Italian “facebook friend” of mine posted several days ago.2

On the margins, firstly, I’d like to mention that I don’t share Parise’s affection (which will be made clear in his essay below) for the beauty of Trotsky’s design of the Bolshevik Red Army uniforms.3 That aside, I must say that what struck me is the wit and shrewdness of Parise oozing out of each line of text as well as the message of the essay itself. It is a piece of critical intelligence and absolute clarity, to be read and re-read in order to better live in this society that distracts us from the essential.4

Secondly, as a wise man wrote: “It is distasteful to hear well-fed people extolling the virtues of peoples that suffer from poverty. Poverty, when it destroys the flesh and the spirit, is no creator of positive values. Periods of want, famine and restrictions, though they call forth gestures of solidarity, also give rise to the worst forms of exploitation—black market, suddenly acquired rights and so on. On a more fundamental plane, poverty can affect the creative faculties, sometimes irreversibly. I have no desire to confuse adversity that degrades with adversity that ennobles.”5

That having been made clear, the essay follows below. It comes in my own unofficial English translation (the footnotes in the English version of the text are my own), followed by the original in Italian, included here because I know that at least two of “The Flying Fish” readers are fluent in the language of Parise.6

Let us attend. Let us hear how with clear, rebellious, poetic answers, as befitting a great writer, Goffredo Parise responds to his readers in Italy of the 1970s. Although almost five decades have passed since the article was written, and although we might be living not in Italy, but Illinois, Ibiza, Inverness, or Irkutsk, do Parise’s reflections remain relevant?

The Remedy Is Poverty

This time I will not respond ad personam, I will speak to everyone, but particularly to those readers who have bitterly reproached me for two sentences of mine: “The poor are always right”, written a few months ago, and the other: “The remedy (for everything) is poverty. Go back? Yes, go back”, written in my last article.

For the first one they wrote that I am ‘a communist’, for the second one some left-wing readers accuse me of playing into the hands of the rich and lash out at me for my hatred of consumption. They say that the lower classes also have the right to ‘consume’.

Right-wingers, let’s call them that, use the following logic: without consumption there is no production, without production unemployment and economic disaster. On both sides, for demagogic or pseudo-economic reasons, everyone agrees that consumption is prosperity, and I respond to them with the title of this article.

Our country has become accustomed to the belief that it is (not being) too rich. At all social levels, because consumption and waste level out and social distinctions disappear, and so does the deepest and most historical sense of ‘class’. We do not only consume obsessively: we behave like starving neurotics who throw themselves on food (consumption) nauseatingly. The spectacle of mass restaurants (especially in the provinces) is unbearable. The quantity of food is enormous, other than price increases. Our national ‘ideology’, especially in the North, consists of hangars full of people throwing themselves on food. The crisis? Where do you see the crisis? The rag (clothing) shops are overflowing, if petrol increased to one thousand lira everyone would still buy it. Strikes would take place in order to pay for petrol. All our ideals seem to be concentrated in the mindless buying of objects and food. There is already talk of hoarding food and clothing. This is our ideology today. And now we come to poverty.

Poverty is not misery, as my leftist objectors believe. Poverty is not ‘communism’, as my crude right-wing objectors believe.

Poverty is an ideology, political and economic. Poverty is enjoying minimum and necessary goods, such as necessary and not superfluous food, necessary clothing, necessary and not superfluous housing. Poverty and national necessity are public means of locomotion, necessary is the health of one’s legs to walk, superfluous is the car, motorbikes, the famous and cretinous ‘yachts’.

Poverty means, above all, realising exactly (also in the economic sense) what one buys, the relationship between quality and price: that is, knowing how to choose well and minutely what one buys because it is necessary, knowing the quality, the material of which the necessary objects are made. Poverty means refusing to buy junk, fake stuff, stuff that lasts for nothing and must last for nothing in homage to the silly law of fashion and the turnover of consumption to maintain, or increase, production.

Poverty means savouring (not simply swallowing in a neurotically obedient manner) food: bread, oil, tomatoes, pasta, wine, which are the products of our country; by learning about these products, one also learns to distinguish the fakes and he protests, he refuses. Poverty means, in short, elementary education in the things that are useful and also enjoyable in life. Many people no longer know how to distinguish wool from nylon, linen from cotton, veal from beef, a cretin from an intelligent one, a sympathetic from an antipathic one, because our only culture is the flat and phantom uniformity of faces and voices and television language. Our entire country, which was once agricultural and artisan (i.e. cultured), no longer knows how to distinguish anything, has no elementary education of things because it no longer has poverty.

Our country just buys. It trusts idiotically ‘di Carosello’ (see Carosello7 and then go to bed, is our evening prayer) and not its own eyes, its own mind, its own palate, its own hands, and its own money. Our country is one big market of neurotics all alike, poor and rich, who buy, buy, without knowing anything, and then throw away and then buy again. Money is no longer an economic instrument, necessary to buy or sell things useful in life, a tool to be used sparingly and avariciously. No, it is something abstract and religious at the same time, an end, an endowment, like saying: I have money, to buy stuff, how good I am, how successful my life is, this money must increase, it must fall from the sky or from the banks that until yesterday lent it in a whirlwind of mortgages (once called debts) that give the illusion of wealth and instead are slavery. Our country is full of people all happy to take on debts because the lira is devalued and so debts will cost less as the years go by.

Our country is an enormous shop of unnecessary rags (because they are rags that are in fashion), expensive and compulsory. Let the objectors on the left and the right, the ‘labelling’ people, get it into their heads, and write to me in absolutely identical linguistic terms, that the same applies to ideologies. Never has there been such a waste of this word, reduced by lack of ideological action not only to pure phoniness, to flatus vocis8 but, that too, to an object of superfluous consumption.

Young people ‘buy’ ideology at the ideological rag market just as they buy blue jeans at the sociological rag market (i.e. out of obligation, out of social dictatorship). Young people don’t know anything any more, they don’t know the quality of the things necessary to life because their fathers despised it in the euphoria of well-being. The boys know that at a certain age (theirs) there are social and ideological obligations which, naturally, they are obliged to obey, no matter what their ‘quality’, their real necessity, matters. Pasolini is right when he speaks of a new fascism without history. There is, in the nauseating market of the superfluous, also ideological and political snobbery (there is everything, see extremism) that is served and publicised as the elite, as the difference and differentiation from the mass ideological market represented by the traditional parties in government and opposition. The mundane obligation imposes the ideological and political boutique, the cliques, this idiocy of 1968 France, the birth date of the ideological and political grand marché aux puces9 of these years. Today, the most snobbish among them are undifferentiated criminals, poor and desperate children of consumption.

Poverty is the opposite of all this: it is knowing things by necessity. I know I am falling into heresy for the ovine mass of consumers of everything by saying that poverty is also physical health and self-expression and freedom and, in a word, aesthetic pleasure. Buying an object because the quality of its material, its shape in space, excites us.

The same rule applies to ideologies. Choose an ideology because it is more beautiful (as well as more ‘correct’, as linguistic rag market dictates). Indeed, beautiful because it is correct and correct because it is known in its real quality. The Red Army uniform designed by Trotsky in 1917, the huge grey-green sheep’s wool coat, as thick as felt, with the pointy cap and the crude red cloth star hand-stitched on the front, was not only right (then) and revolutionary and popular, it was also beautiful in a way that no Soviet military uniform was. Because it was poor and necessary. Poverty, finally, you begin to learn, is an infinitely richer hallmark today than wealth. But let’s not put it on the market too, like blue jeans with patches on the arse that cost a lot of money. Let’s keep it as personal property, private property, and indeed as wealth, capital: the only national capital that now, I am deeply convinced, will save our country.

THE END

«Il rimedio è la povertà»

Questa volta non risponderò ad personam, parlerò a tutti, in particolare però a quei lettori che mi hanno aspramente rimproverato due mie frasi: «I poveri hanno sempre ragione», scritta alcuni mesi fa, e quest’altra: «Il rimedio (di tutto) è la povertà. Tornare indietro? Sì, tornare indietro», scritta nel mio ultimo articolo.

Per la prima hanno scritto che sono «un comunista», per la seconda alcuni lettori di sinistra mi accusano di fare il gioco dei ricchi e se la prendono con me per il mio odio per i consumi. Dicono che anche le classi meno abbienti hanno il diritto di «consumare».

Lettori, chiamiamoli così, di destra, usano la seguente logica: senza consumi non c’è produzione, senza produzione disoccupazione e disastro economico. Da una parte e dall’altra, per ragioni demagogiche o pseudo-economiche, tutti sono d’accordo nel dire che il consumo è benessere, e io rispondo loro con il titolo di questo articolo.

Il nostro paese si è abituato a credere di essere (non ad essere) troppo ricco. A tutti i livelli sociali, perché i consumi e gli sprechi livellano e le distinzioni sociali scompaiono, e così il senso più profondo e storico di «classe». Noi non consumiamo soltanto, in modo ossessivo: noi ci comportiamo come degli affamati nevrotici che si gettano sul cibo (i consumi) in modo nauseante. Lo spettacolo dei ristoranti di massa (specie in provincia) è insopportabile. La quantità di cibo è enorme, altro che aumenti dei prezzi. La nostra «ideologia» nazionale, specialmente nel Nord, è fatta di capannoni pieni di gente che si getta sul cibo. La crisi? Dove si vede la crisi? Le botteghe di stracci (abbigliamento) rigurgitano, se la benzina aumentasse fino a mille lire tutti la comprerebbero ugualmente. Si farebbero scioperi per poter pagare la benzina. Tutti i nostri ideali sembrano concentrati nell’acquisto insensato di oggetti e di cibo. Si parla già di accaparrare cibo e vestiti. Questo è oggi la nostra ideologia. E ora veniamo alla povertà.

Povertà non è miseria, come credono i miei obiettori di sinistra. Povertà non è «comunismo», come credono i miei rozzi obiettori di destra.

Povertà è una ideologia, politica ed economica. Povertà è godere di beni minimi e necessari, quali il cibo necessario e non superfluo, il vestiario necessario, la casa necessaria e non superflua. Povertà e necessità nazionale sono i mezzi pubblici di locomozione, necessaria è la salute delle proprie gambe per andare a piedi, superflua è l’automobile, le motociclette, le famose e cretinissime «barche».

Povertà vuol dire, soprattutto, rendersi esattamente conto (anche in senso economico) di ciò che si compra, del rapporto tra la qualità e il prezzo: cioè saper scegliere bene e minuziosamente ciò che si compra perché necessario, conoscere la qualità, la materia di cui sono fatti gli oggetti necessari. Povertà vuol dire rifiutarsi di comprare robaccia, imbrogli, roba che non dura niente e non deve durare niente in omaggio alla sciocca legge della moda e del ricambio dei consumi per mantenere o aumentare la produzione.

Povertà è assaporare (non semplicemente ingurgitare in modo nevroticamente obbediente) un cibo: il pane, l’olio, il pomodoro, la pasta, il vino, che sono i prodotti del nostro paese; imparando a conoscere questi prodotti si impara anche a distinguere gli imbrogli e a protestare, a rifiutare. Povertà significa, insomma, educazione elementare delle cose che ci sono utili e anche dilettevoli alla vita. Moltissime persone non sanno più distinguere la lana dal nylon, il lino dal cotone, il vitello dal manzo, un cretino da un intelligente, un simpatico da un antipatico perché la nostra sola cultura è l’uniformità piatta e fantomatica dei volti e delle voci e del linguaggio televisivi. Tutto il nostro paese, che fu agricolo e artigiano (cioè colto), non sa più distinguere nulla, non ha educazione elementare delle cose perché non ha più povertà.

Il nostro paese compra e basta. Si fida in modo idiota di Carosello (vedi Carosello e poi vai a letto, è la nostra preghiera serale) e non dei propri occhi, della propria mente, del proprio palato, delle proprie mani e del proprio denaro. Il nostro paese è un solo grande mercato di nevrotici tutti uguali, poveri e ricchi, che comprano, comprano, senza conoscere nulla, e poi buttano via e poi ricomprano. Il denaro non è più uno strumento economico, necessario a comprare o a vendere cose utili alla vita, uno strumento da usare con parsimonia e avarizia. No, è qualcosa di astratto e di religioso al tempo stesso, un fine, una investitura, come dire: ho denaro, per comprare roba, come sono bravo, come è riuscita la mia vita, questo denaro deve aumentare, deve cascare dal cielo o dalle banche che fino a ieri lo prestavano in un vortice di mutui (un tempo chiamati debiti) che danno l’illusione della ricchezza e invece sono schiavitù. Il nostro paese è pieno di gente tutta contenta di contrarre debiti perché la lira si svaluta e dunque i debiti costeranno meno col passare degli anni.

Il nostro paese è un’enorme bottega di stracci non necessari (perché sono stracci che vanno di moda), costosissimi e obbligatori. Si mettano bene in testa gli obiettori di sinistra e di destra, gli «etichettati» che etichettano, e che mi scrivono in termini linguistici assolutamente identici, che lo stesso vale per le ideologie. Mai si è avuto tanto spreco di questa parola, ridotta per mancanza di azione ideologica non soltanto a pura fonia, a flatus vocis ma, anche quella, a oggetto di consumo superfluo.

I giovani «comprano» ideologia al mercato degli stracci ideologici così come comprano blue jeans al mercato degli stracci sociologici (cioè per obbligo, per dittatura sociale). I ragazzi non conoscono più niente, non conoscono la qualità delle cose necessarie alla vita perché i loro padri l’hanno voluta disprezzare nell’euforia del benessere. I ragazzi sanno che a una certa età (la loro) esistono obblighi sociali e ideologici a cui, naturalmente, è obbligo obbedire, non importa quale sia la loro «qualità», la loro necessità reale, importa la loro diffusione. Ha ragione Pasolini quando parla di nuovo fascismo senza storia. Esiste, nel nauseante mercato del superfluo, anche lo snobismo ideologico e politico (c’è di tutto, vedi l’estremismo) che viene servito e pubblicizzato come l’élite, come la differenza e differenziazione dal mercato ideologico di massa rappresentato dai partiti tradizionali al governo e all’opposizione. L’obbligo mondano impone la boutique ideologica e politica, i gruppuscoli, queste cretinerie da Francia 1968, data di nascita del grand marché aux puces ideologico e politico di questi anni. Oggi, i più snob tra questi, sono dei criminali indifferenziati, poveri e disperati figli del consumo.

La povertà è il contrario di tutto questo: è conoscere le cose per necessità. So di cadere in eresia per la massa ovina dei consumatori di tutto dicendo che povertà è anche salute fisica ed espressione di se stessi e libertà e, in una parola, piacere estetico. Comprare un oggetto perché la qualità della sua materia, la sua forma nello spazio, ci emoziona.

Per le ideologie vale la stessa regola. Scegliere una ideologia perché è più bella (oltre che più «corretta», come dice la linguistica del mercato degli stracci linguistici). Anzi, bella perché giusta e giusta perché conosciuta nella sua qualità reale. La divisa dell’Armata Rossa disegnata da Trotzky nel 1917, l’enorme cappotto di lana di pecora grigioverde, spesso come il feltro, con il berretto a punta e la rozza stella di panno rosso cucita a mano in fronte, non soltanto era giusta (allora) e rivoluzionaria e popolare, era anche bella come non lo è stata nessuna divisa militare sovietica. Perché era povera e necessaria. La povertà, infine, si cominci a impararlo, è un segno distintivo infinitamente più ricco, oggi, della ricchezza. Ma non mettiamola sul mercato anche quella, come i blue jeans con le pezze sul sedere che costano un sacco di soldi. Teniamola come un bene personale, una proprietà privata, appunto una ricchezza, un capitale: il solo capitale nazionale che ormai, ne sono profondamente convinto, salverà il nostro paese.

The essay comes from the anthology Dobbiamo disobbedire (We Must Disobey), edited by Silvio Perrella and published by Adelphi (2013), see here.

A few of my findings realted to the text and its Author: The essay first appeared as an article on 30 June 1974 in the Milanese Corriere della Sera. For almost two years, 1974 and 1975, Parise held a column on the second Sunday page of the Corriere entirely dedicated to dialogue with readers. He seemingly succumbed to the illusion of establishing a ‘democratic’ dialogue, made up of exchange on an equal footing based on ‘mutual curiosity’.

Subsequently, by his own admission, Parise interrupted his collaboration with the newspaper, because not enough of the responses he received were truly interesting to him: they were unable to arouse his curiosity as a critic. But this makes his surrender even more interesting if we compare it with our ‘modern’ anti-socially-networked and trans-embedded comment sections of Twitters, Facebooks, and YouTubes, in their “interface” (at our fingertips at all times) of the QWERTY and LCD-screen hybrid chimeras that turn all minds young and old into mush while feeding the moloch of metadata. It seems to me that Goffredo Parise understood a long ago what the true role of the writer-intellectual is: to observe, narrate, denounce without filters. Seemingly, Parise held back nothing of what he captured in his everyday life or during his travels to the most dangerous places in the world, visited during his career as a reporter—similar to Pier Paolo Pasolini.

It may be a worthy mention that, as David Grieco writes (in 2020), Parise had The Remedy Is Poverty published in order to come to the rescue of Pasolini:

The son of a single mother, Goffredo Parise was adopted at the age of eight, in 1937, by journalist Osvaldo Parise, editor of the Giornale di Vicenza. As a teenager, he took part in the Resistance, and at the end of the war he too became a journalist, soon discovering his innate ability to tell stories, often supported by real-life testimonies.

While winning back-to-back literary prizes with his novels, Parise never stopped travelling the world, producing extraordinary reportages and immersing himself like an authentic anthropologist in the customs and habits of the populations he encountered.

A path very similar to that of Pier Paolo Pasolini.

Pasolini adored Parise unconditionally. Parise reciprocated him but not without a hint of reluctance because he detested homosexuality.

Goffredo Parise, an apolitical and non-ideological man, wrote this article [The Remedy Is Poverty] (…) to come to the rescue of Pier Paolo Pasolini, pilloried by all for his apocalyptic editorials against the plague of consumerism in the Corriere della Sera. Parise supported and reworked Pasolini’s thesis, making his own an atavistic peasant wisdom and keeping himself politically equidistant from the right as well as the left.

This article is a true masterpiece, tremendously fitting to the world crisis we are experiencing due to an unknown virus that seems to be the three-dimensional photograph of all our mistakes.

As a digression, a small joke: Do you know what is black and white, and red all over? Trotsky in a tuxedo.

And, in my humble view, today’s so-called journalists and op-ed writers have much to learn from Goffredo Parise, e.g. the frankness, the courage of words, the non-compliance with political winds passed by the ‘replacist’ (i.e. of Renaud Camus’ The Great Replacement-kind) global conglomerate of all the we-all-know-who-they-are. Perhaps today, we (the present Reader and I) do miss some good old master writers and lecturers, as well as journalists, who’d know the weight of words, who still have the courage to tell us that sometimes we must disobey. Or tell us that the remedy to our mass-produced and mass-consumed painful living reality of artifacts and “information” and afflictions resulting from the contemporary everything-new-is-better-than-everything-old way of seeing man and the world isn’t found in emotional Netflix documentaries or transcendental meditation apps but… in the poverty spelled out by Parise.

Poverty: Wealth of Mankind, Albert Tévoédjrè, (1979) p.10.

A crying shame it is that so very little of Parise’s writing has been translated to English.

During the past few days that I have spent reading more of Parise, as well as what has been said about him, I had no choice but to rely on the ‘DeepL’ to help me with translations from the Italian language. I cleaned up the translation to the best of my ability. (Please, kindly post any corrections in the comment section below).

Carosello (“Carousel”) was an Italian television advertising show broadcast on RAI from 1957 to 1977. The series mainly showed short sketch comedy films using live action, various types of animation, and puppetry. It had an audience of about 20 million viewers. See Wikipedia here

Flatus vocis: Latin for “breath of the voice” or “voices of air”. A mere name, word, or sound without a corresponding objective reality. An expression used by the nominalists of universals.

Grand marché aux puces: A grand flea market.